The stock market can be an intimidating place: it’s real money on the line, there’s an overwhelming amount of information to follow, and people have lost fortunes in it very quickly.

But it’s also a place where thoughtful investors have long accumulated a lot of wealth.

The primary difference between positive and negative outcomes is related to misconceptions about the stock market that can lead people to make poor investment decisions.

With that in mind, I present to you ten truths about the stock market.1

1. The long game is undefeated

There’s nothing the stock market hasn’t overcome.

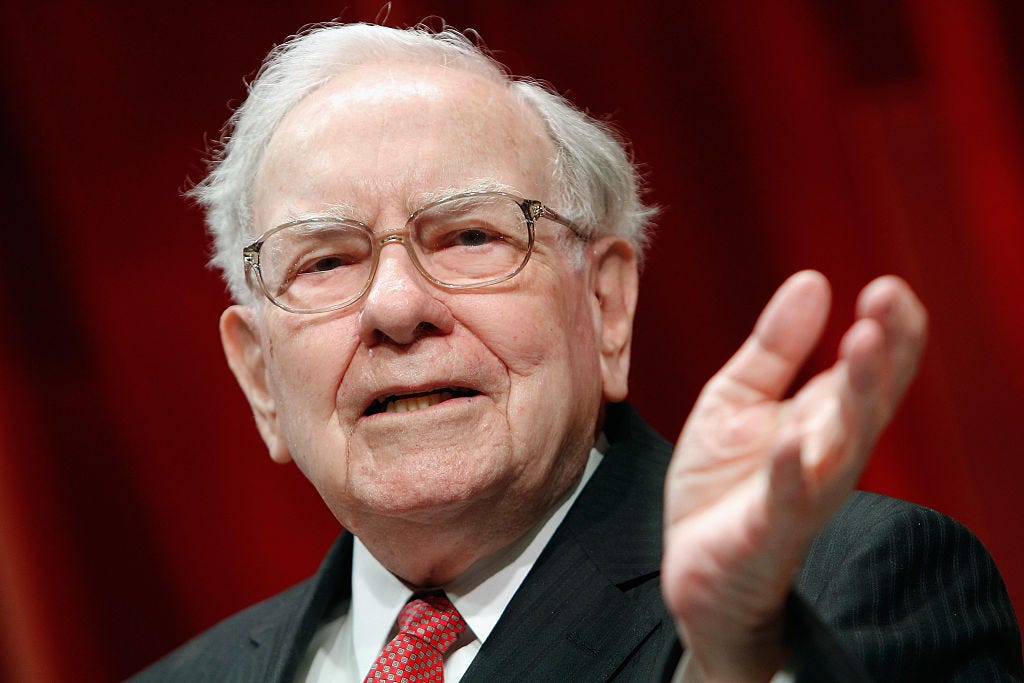

“Over the long term, the stock market news will be good,” billionaire investor Warren Buffett, the greatest investor in history, wrote in an op-ed for The New York Times during the depths of the global financial crisis. “In the 20th century, the United States endured two world wars and other traumatic and expensive military conflicts; the Depression; a dozen or so recessions and financial panics; oil shocks; a flu epidemic; and the resignation of a disgraced president. Yet the Dow rose from 66 to 11,497.”

Since that op-ed was published, the market emerged from the global financial crisis. It also overcame a U.S. credit rating downgrade and a global pandemic among many other challenges. The Dow closed Thursday at 34,912, just 2% from its all-time high.

Btw, historically you didn’t have to wait a hundred years for positive returns. Since 1926, there’s never been a 20-year period where the stock market didn’t generate a positive return.

While stocks usually go up over much shorter periods, the odds of positive returns improve as you lengthen your time horizon.

For more, read: In the stock market, time pays ⏳ and A very long-term chart of U.S. stock prices usually going up 📈

2. You can get smoked in the short-term

Bull markets come with lots of bumps in the road.

While the S&P 500 has usually generated positive annual returns, it’s also seen an average drawdown (i.e. a decline from its high) of 14% during those years.

The chart below from JP Morgan Asset Management does a nice job illustrating this. The grey bars represent each calendar year’s return and the red dots represent the intra-year drawdowns.

Bear markets are no picnic either: They can happen quickly, like the S&P500’s 34% drop from February 19, 2020 to March 23, 2020; and they can happen painfully slowly, like the 57% decline from October 9, 2007 to March 9, 2009.

Investing for long-term returns means being able to stomach a lot of intermediate volatility.

For more, read: Stomach-churning stock market sell-offs are normal🎢, My favorite visualization of short-term stock market performance 📊, and Bear markets and a truth about investing 🐻

3. Don’t ever expect average

At some point in your life, you probably heard that the stock market generates about 10% annual returns on average.

While that may be true in the long run, the market rarely delivers an average return in a given year.

Check out the chart below from Ritholtz Wealth Management’s Ben Carlson. It plots the S&P 500’s annual returns since 1926. If 10%-ish returns were commonplace, you’d see a tight horizontal line of dots just above the x-axis.

This chaotic mess of dots illustrates just how difficult it is to predict what next year’s returns are going to be. This holds true even if you know exactly what’s going to happen in the economy. Outside of the Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis, it’s difficult to make out history’s major economic booms and bust.

The good news is most of the dots are above the black line. Indeed, stocks usually go up.

For more, read: Don't expect average returns in the stock market this year 📊, Don't be afraid of the market's bears 🐻, and 2 telling charts about the stock market's volatile path📉📈

4. Stocks offer asymmetric upside

A stock can only go down by 100%, but there’s no limit to how many times that value can multiply going up.

Yes, we’ve seen some pretty bad sell-offs in the stock market. But it’s gone up manyfold more. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s offered. From its low of 666 in March 2009, the S&P 500 is up more than 6x today.

For more, read: The stock market's incredible asymmetric upside 📈, There's more upside than downside for long-term investors 📈, and Warren Buffett reminds us how picking winning stocks is extraordinarily hard 🤓

5. Earnings drive stock prices

Any long term move in a stock can ultimately be explained by the underlying company’s earnings, expectations for earnings, and uncertainty about those expectations for earnings.

News about the economy or policy moves markets to the degree they are expected to impact earnings. Earnings (a.k.a. profits) are why you invest in companies.

For more, read: Earnings are the most important driver of stock prices💰, Peter Lynch made a remarkably prescient market observation in 1994 🎯, and Publicly traded companies are not charities 💸

6. Valuations won’t tell you much about next year

There are many valuation methods that’ll help you estimate whether a stock or stock market is cheap or expensive. We won’t go through all of those here.

While valuation methods may tell you something about long-term returns, most tell you almost nothing about where prices are headed in the next 12 months. Over short periods like this, expensive things can get more expensive and cheap things can get cheaper.

It’s worth noting that prices can be cheap or expensive for extended periods of time. In fact, some folks would argue valuations are not mean-reverting.

For more, read: The stock market's complicated evolving relationship with valuations 📈, Use valuation metrics like the P/E ratio with caution ⚠️, and Goldman Sachs destroys one of the most persistent myths about investing in stocks 🤯

7. There will always be something to worry about

Investing in stocks is risky, which is why the returns are relatively high.

Even in the most favorable market conditions, there will always be something keeping the most risk-averse folks on the sidelines. For more, check out Yahoo Finance Morning Brief’s chart of the decade.

For more, read: Sorry, but uncertainty will always be high 😰 and Two recent instances when uncertainty seemed low and confidence was high 🌈

8. The most destabilizing risks are the ones people aren’t talking about

Surveys of market participants will yield lists of top risks, and ironically the most commonly cited risks are the ones that are already priced into the markets.

It’s the risks no one is talking about or few are concerned about that’ll rock markets when they come to surface.

For more, read: The most destabilizing risks to the stock market 📉, For markets, there’s one thing worse than bad news 📉📈, and Taking stock of Corporate America’s ‘Risk Factors’⚠️

9. There’s a lot of turnover in the stock market

Just as most businesses don’t last forever, most stocks aren’t in the market forever. The S&P 500 sees lots of turnover (i.e. failing businesses get dropped and up-and-coming businesses get added).

In fact, it’s the addition of new and unexpected companies that have been driving much of the S&P 500’s returns over the past decade.

For more, read: 700+ reasons why S&P 500 index investing isn't very 'passive'💡 and The makeup of the S&P 500 is constantly changing 🔀

10. The stock market is and isn’t the economy

While the U.S. stock market’s performance is closely tied to the trajectory of the U.S. economy, they’re not the same thing.

The economy reflects all of the business being conducted in the U.S. while the market reflects the performance of the biggest companies — which typically have access to lower-cost financing and have the scale to source goods and labor more cheaply.

Importantly, many of these bigger companies that make up the stock market do at least some business overseas where growth prospects may be better than in the U.S.

For more, read: The stock market is not the economy in an important way 🌎, 4 key observations about the U.S. stock market to remember 📊, and The 'critical' consumer shift that could define stock market performance in 2024 🔀

What all of this means

We could very well be on the brink of a dreadful, multi-year long bear market. Who knows?

However, the stock market has an upward bias.

This makes sense if you think about it. There are way more people who want things to be better, not worse. And that demand incentivizes entrepreneurs and businesses to develop better goods and services.

And the winners in this process get bigger as revenue grows. Some even get big enough to get listed in the stock market. As revenue grows, so do earnings.

And earnings drive stock prices.

The “stock market” is a general term usually used to refer to the major U.S. indices: the Dow Jones Industrial Index, the S&P 500, and the Nasdaq. When I refer to “stocks,” I’m usually referring to the S&P 500. When discussing specific stats, I’ll be explicit about what I’m talking about.

japan and europe markets are barely upward biased even though their CB BS are higher than usa as % of GDP, why ?....was rangebound for decades , so was their EPS