Economic data can often be both 'worse' and 'good' 🌦️

Plus a charted review of the macro crosscurrents 🔀

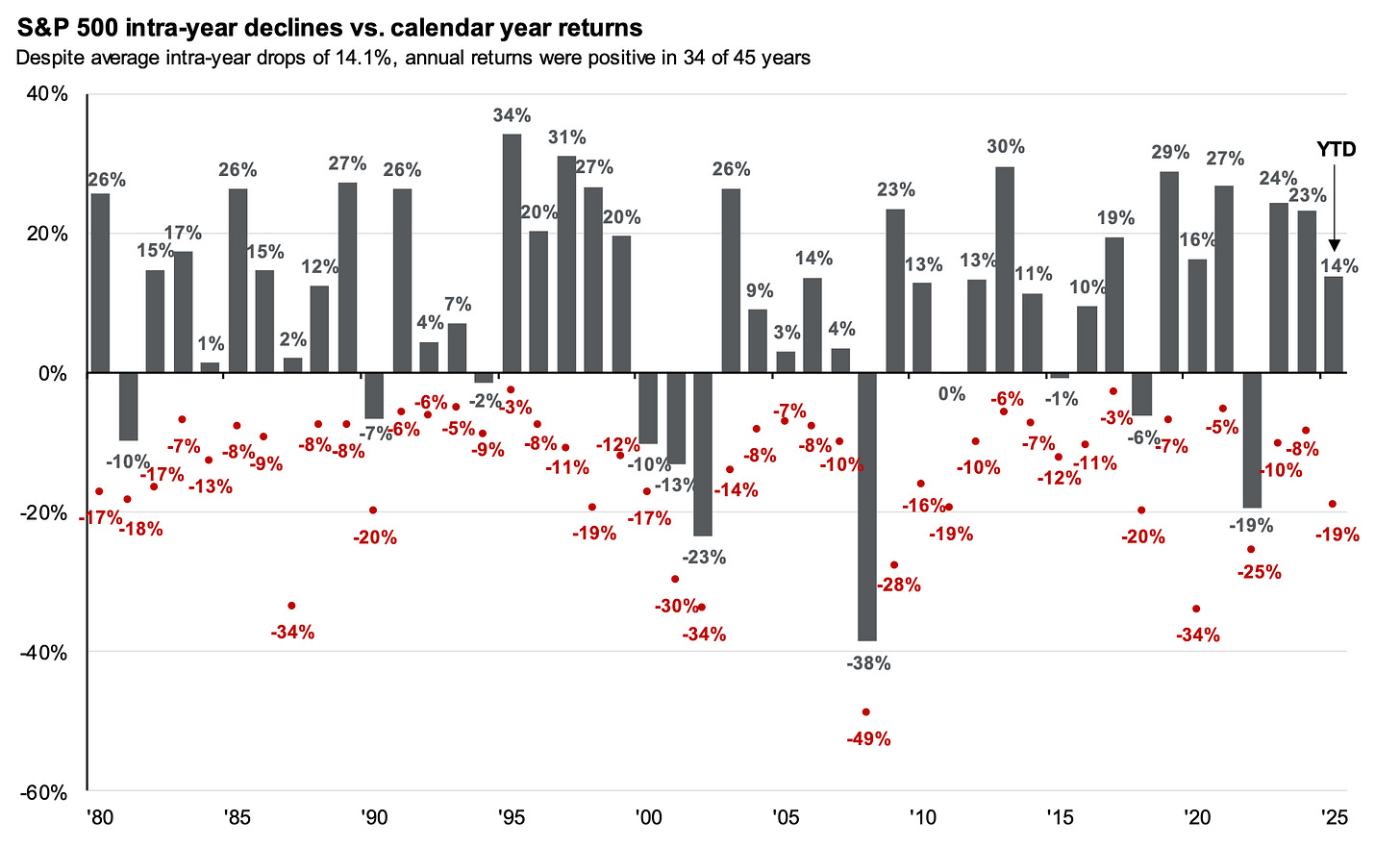

📉The stock market declined last week, shedding 1.4% to end at 6,836.17. The index is now down 2.0% from its Jan. 27 closing high of 6,978.60 and down 0.1% year-to-date. Is this bad? Read: 2026 could be crappy for the stock market, and that would be normal 📉

-

An economic metric can simultaneously be getting worse and be good. It can also be both better and bad.

That’s because “worse” and “better” are relative terms, while “good” and “bad” are absolute terms.

Kind of like when you’re recovering from illness. You sometimes start feeling better than yesterday while still feeling crummy overall.

Maybe you used to run a six-minute mile. But now it takes you seven minutes. Your time got worse, but it’s not bad.

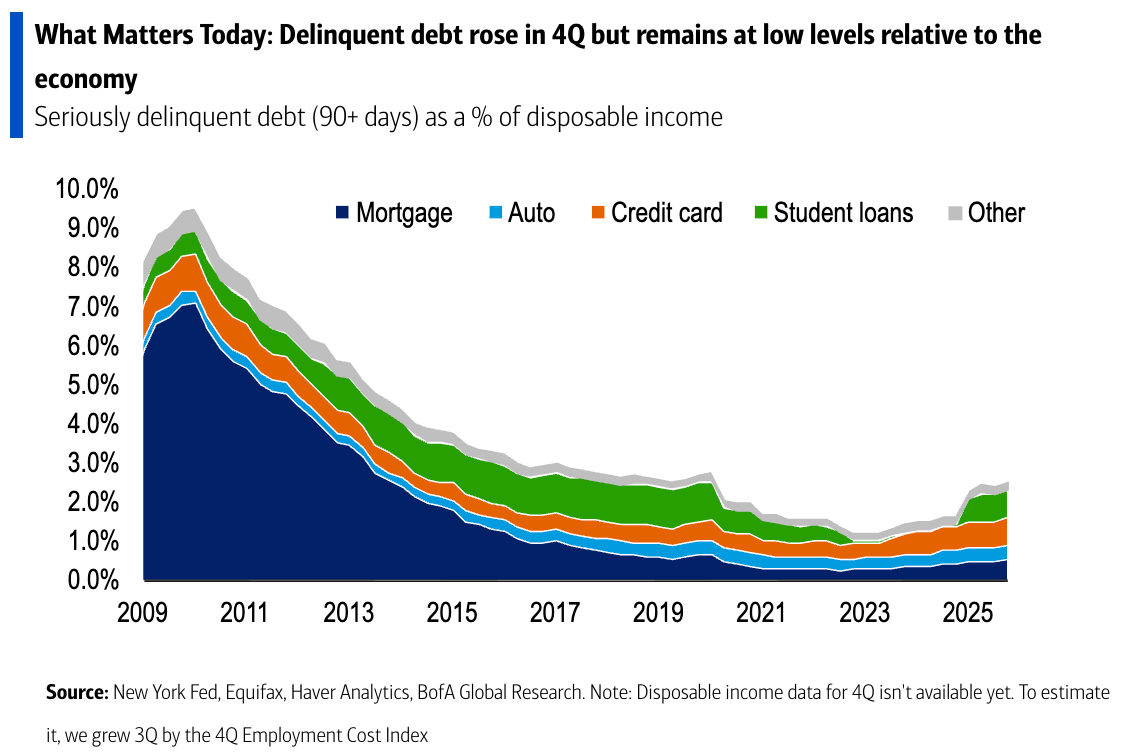

The state of household finances can be described as getting worse, but still good.

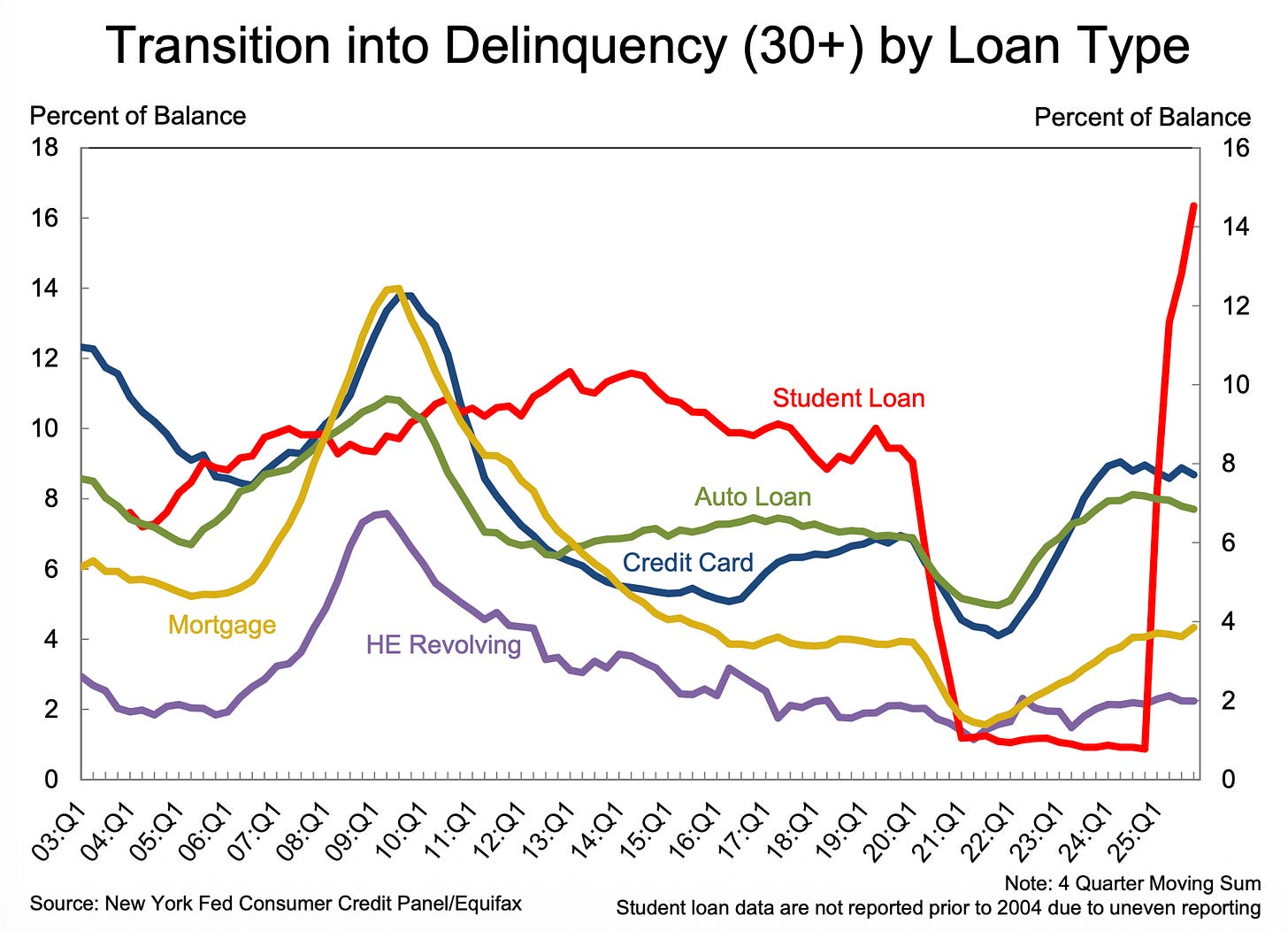

According to the New York Fed’s new Household Debt & Credit report, the amount of mortgage and student loan debt transitioning into early delinquency rose in Q4. Regarding the outsized swing in student loans transitioning into delinquency, NY Fed researchers note that it “reflects continued effects from the resumption of payment reporting following the extended pandemic forbearance period.”

Delinquency rates held mostly steady for auto loans, credit cards, and home equity loans during the period. Still, delinquency rates for all forms of debt have worsened from their lows just a few years ago.

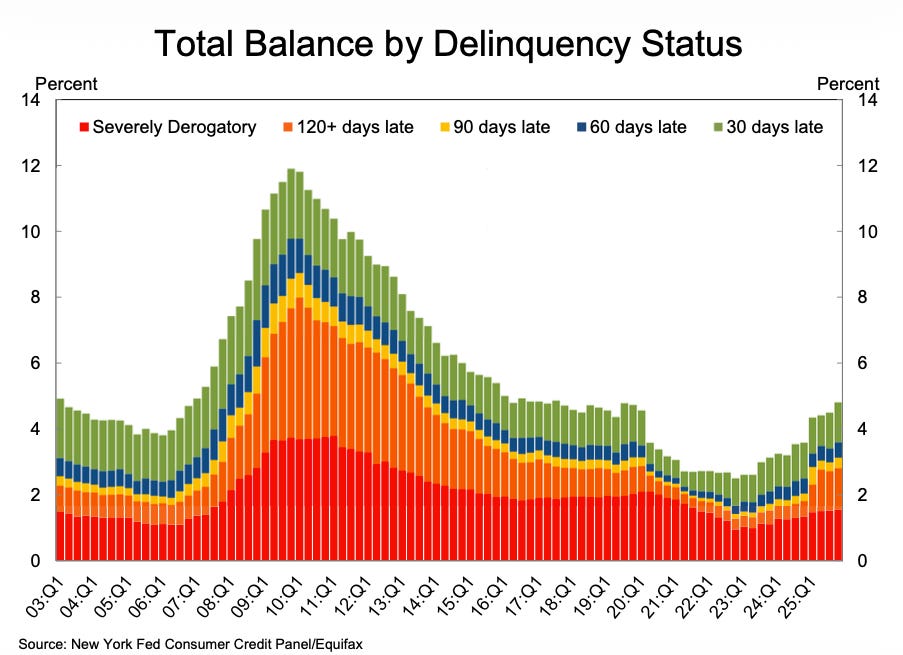

The chart showing the total amount of debt in some stage of delinquency is less alarming than the charts showing the rates of transition into delinquency. Still, 4.8% of outstanding debt, the total amount of debt in delinquency is the highest since 2017.

To be clear, all these metrics have gotten worse. I don’t think anyone’s disputing that.

However, these metrics mostly reflect financial health seen during the prepandemic economic expansion.

In other words, what we’ve experienced in recent years is household finances normalizing from unusually strong levels to relatively worse levels that are arguably still good.

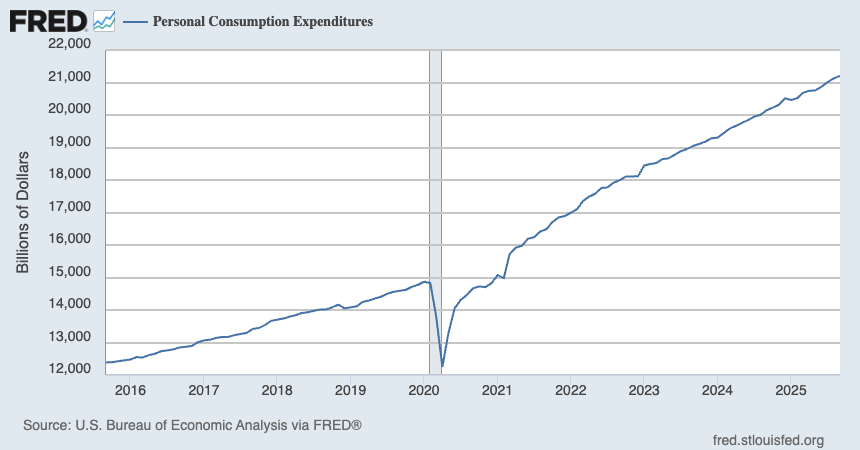

This explains why economic activity metrics like personal consumption expenditures have continued to climb during this period of deteriorating finances. Americans have had money, and they’ve been spending it.

“Consumer debt grabbed headlines [Tuesday] as total delinquent debt rose to 4.8% in 4Q 25, its highest since 2017,” BofA’s Shruti Mishra wrote. “This raised some alarm bells, particularly with mortgage delinquencies ticking up for lower-income households. However, the risk posed by increasing delinquent debt remains limited, in our view. Seriously delinquent debt-to-income is around 2.5%, roughly in line with levels seen in 4Q 19 and far from the near 10% levels seen in 2009 and 2010.”

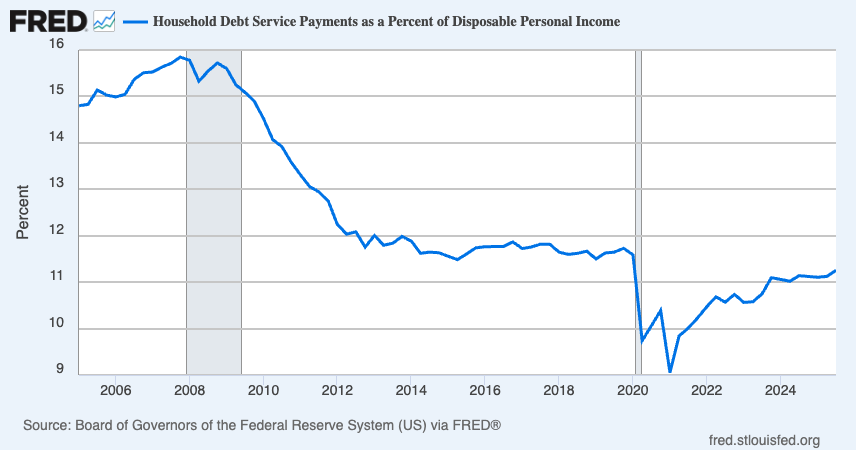

Another popular way to look at debt relative to income is household debt service payments as a percent of disposable income. This is a metric that has been deteriorating for years. But on an absolute basis, it remains pretty strong.

Context matters, but don’t get complacent 🙋🏻♂️

The point of this discussion is to remember that when considering data that’s getting better or worse, you should zoom out and also check whether that data is good or bad.

As you’ll see below in the review of macro crosscurrents, this practice can apply to many metrics. Inflation rates are improving, but remain above the Fed’s target. Job creation rates have fallen significantly, yet remain positive. Retail sales growth has stalled but is hovering at record levels.

This is not to say we should be celebrating negative developments. In fact, worsening trends bear watching as they may eventually reach levels that are arguably bad.

-

Related from TKer:

🎲🎰 See me in Las Vegas!

I’ll be leading a breakout session at The MoneyShow TradersExpo in Las Vegas. The conference runs from Feb. 23 to 25. Sign up here!

Review of the macro crosscurrents 🔀

There were several notable data points and macroeconomic developments since our last review:

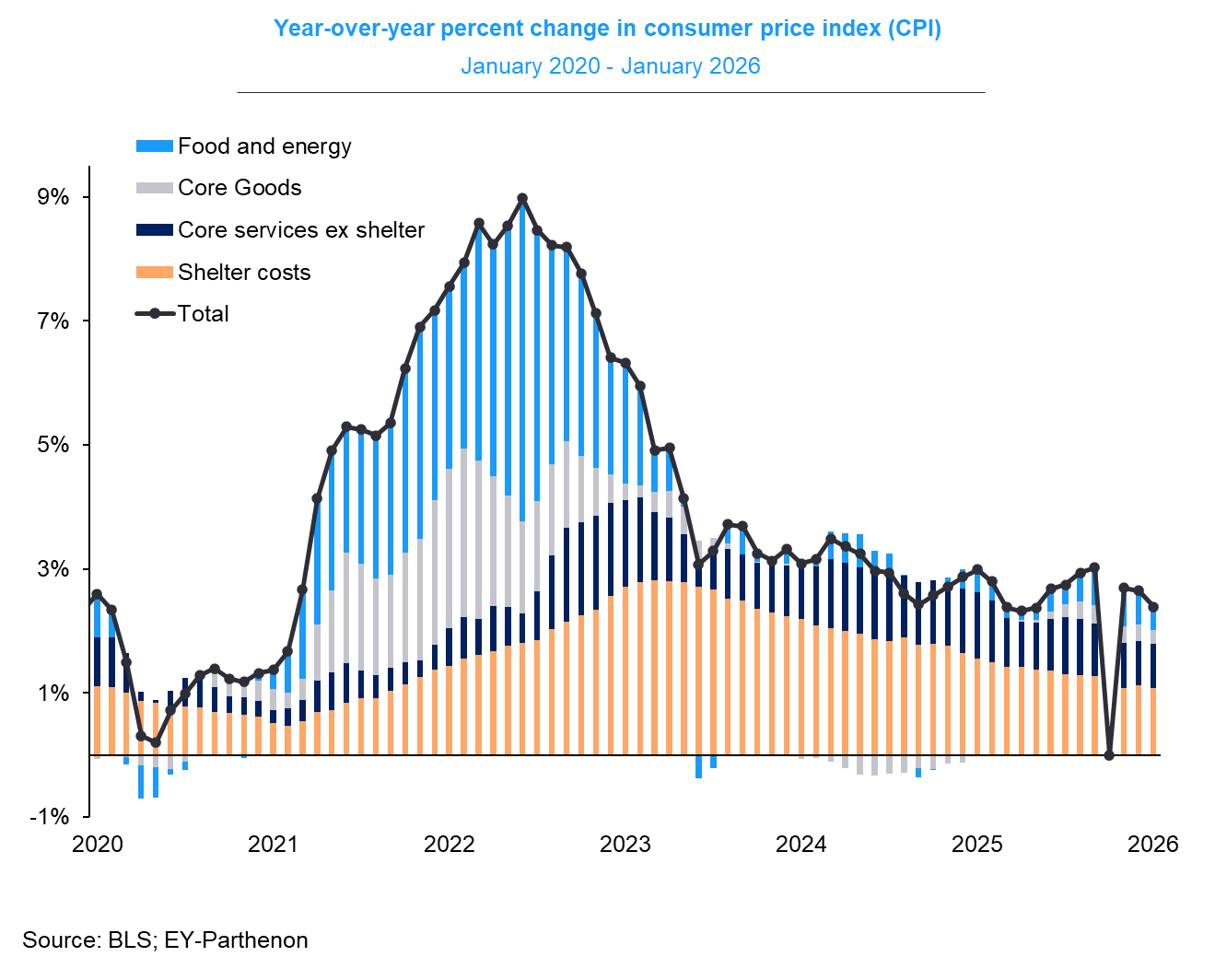

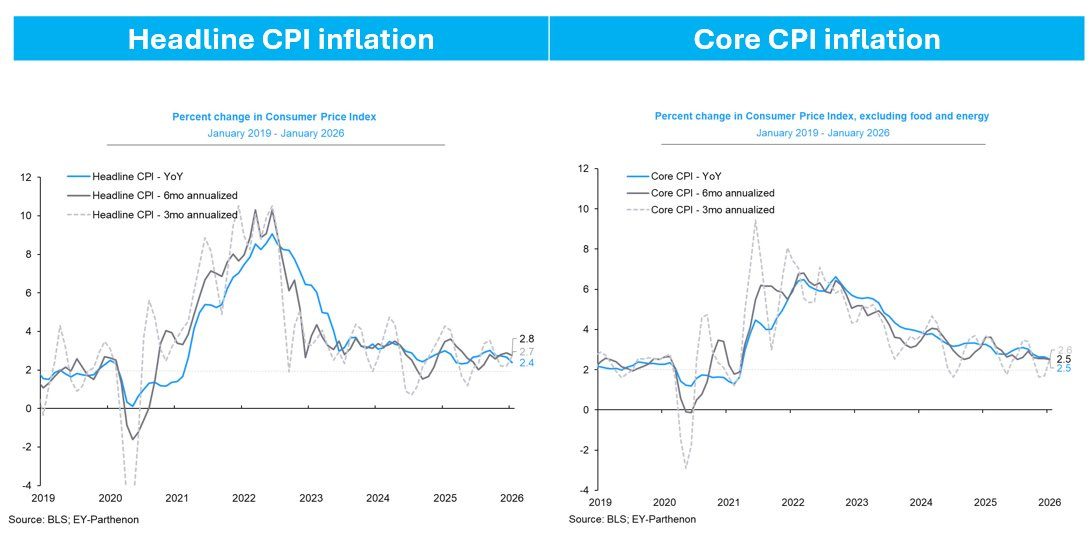

🎈Consumer price inflation appears to cool. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.4% year over year in January, down from 2.7% in the prior month. Adjusted for food and energy prices, core CPI was up 2.5%, a post-pandemic low. (Note: there was no October CPI data due to the government shutdown.)

On a month-over-month basis, CPI was up 0.2%, and core CPI increased 0.3%. If you annualize the three-month trend in the monthly figures — a reflection of the short-term trend in prices — core CPI climbed 2.6%.

While inflation rates remain above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, they are down considerably from peak levels just a few years ago.

For more on the Fed’s impact on markets, read: There’s a more important force than the Fed driving the stock market 💪

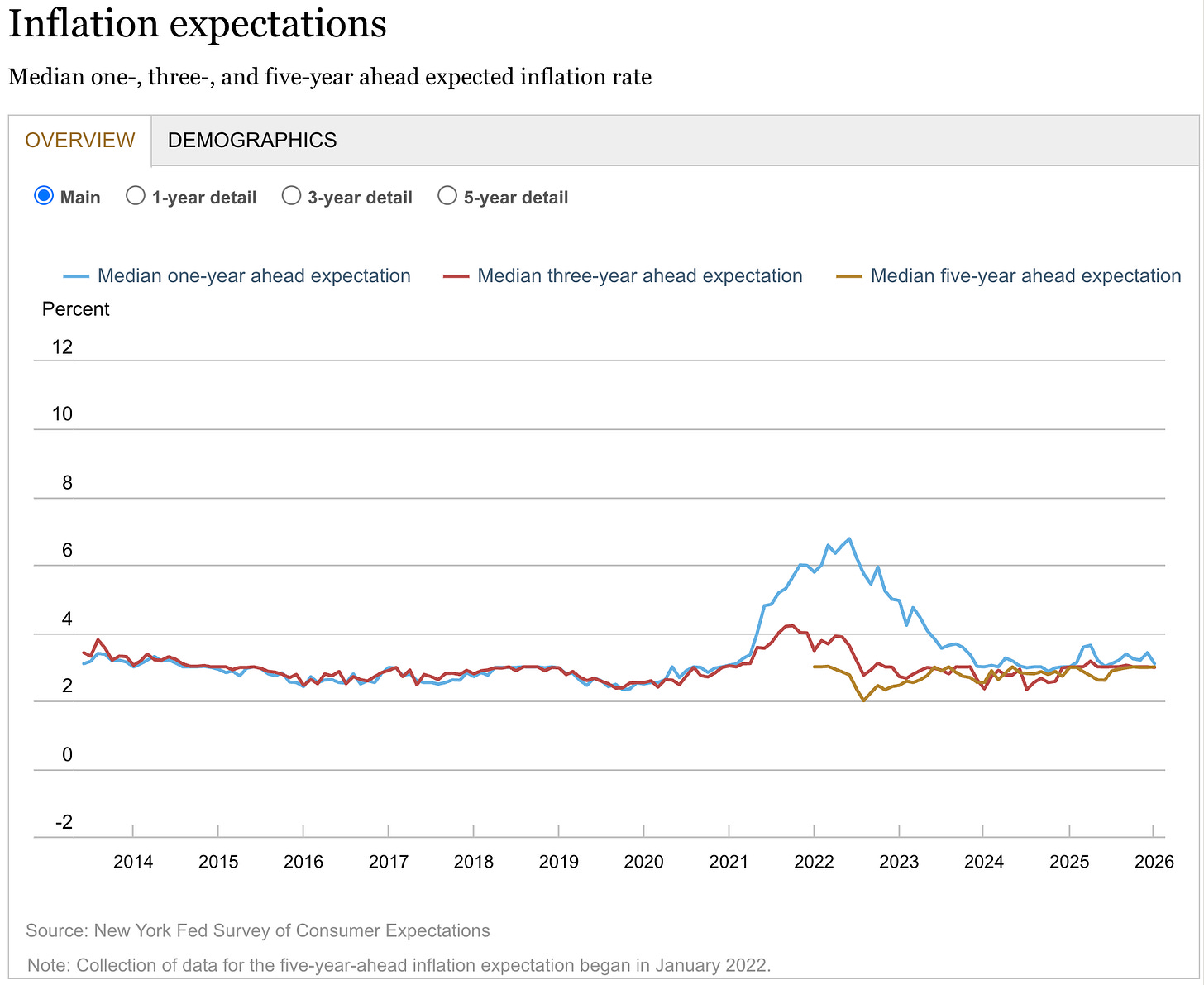

🎈 Inflation expectations could be cooler. From the New York Fed’s January Survey of Consumer Expectations: “Median inflation expectations in January declined by 0.3 percentage point at the one-year-ahead horizon to 3.1% and remained steady at the three-year and five-year-ahead horizons at 3.0%.”

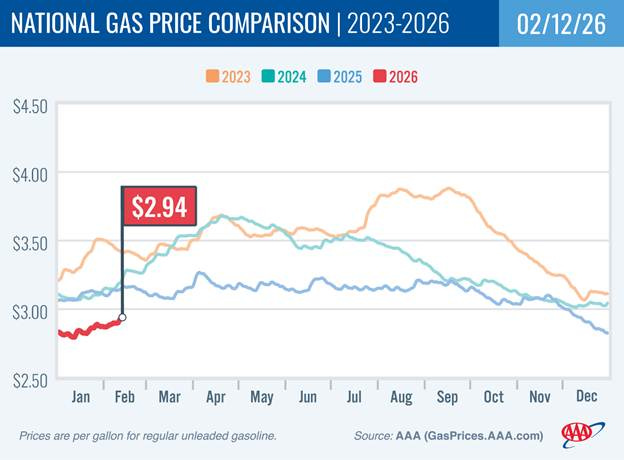

⛽️ Gas prices tick higher, but remain relatively low. From AAA: “Drivers may notice gas prices ticking up slightly ahead of the holiday weekend. The national average for a gallon of regular is up a couple of cents from last week to $2.94. Current prices remain below what they were this time last year when the national average was $3.14.”

For more on energy prices, read: Higher oil prices meant something different in the past 🛢️

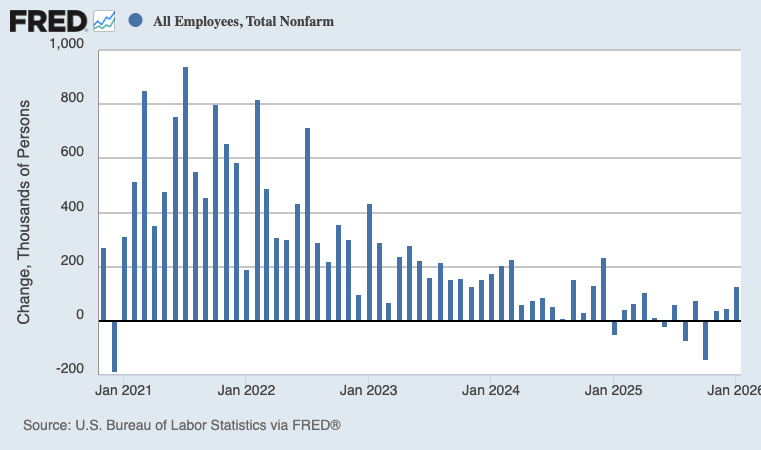

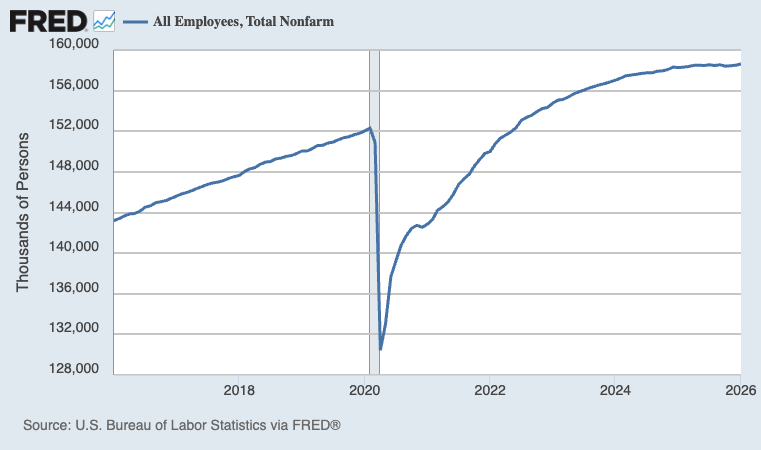

💼 Job creation picked up in January. According to the BLS’s Employment Situation report released on Wednesday, U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January, up from 48,000 jobs in December. The rolling three-month average improved to +73,000.

Total payroll employment climbed to a record 158.6 million jobs in January.

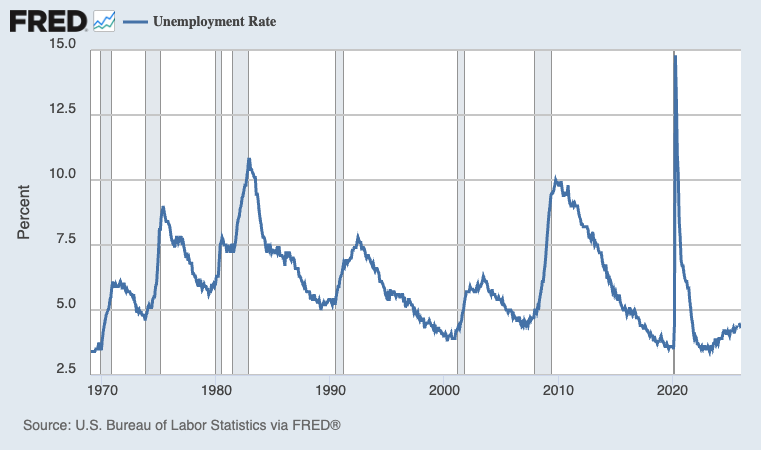

The unemployment rate — that is, the number of workers who identify as unemployed as a percentage of the civilian labor force — declined to 4.3% in January, but remains near the highest level since October 2021.

The labor market continues to create jobs, it clearly isn’t as hot as it used to be.

For more on the labor market, read: We’re at an economic tipping point ⚖️ and 9 once-hot economic charts that cooled 📉

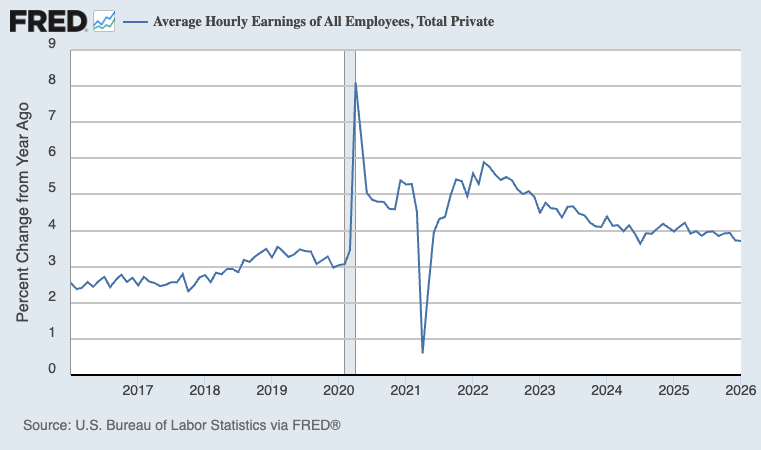

💸 Wage growth cools. Average hourly earnings rose by 0.41% month-over-month in January, up from the 0.05% pace in December. On a year-over-year basis, December’s wages were up 3.7%.

For more on why policymakers are watching wage growth, read: Revisiting the key chart to watch amid the Fed’s war on inflation 📈

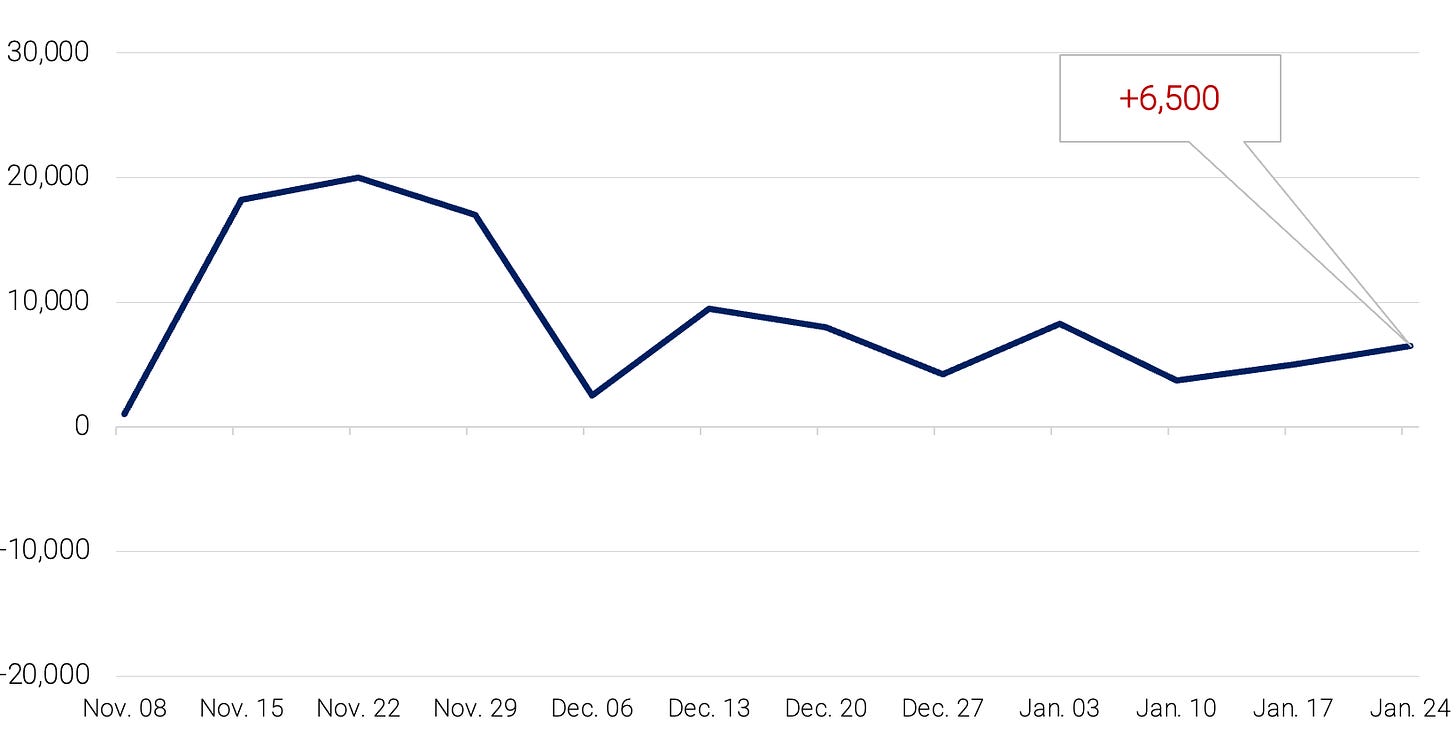

👎 Recent job private job growth has been lackluster. According to payroll processor ADP, private U.S. employers added 6,500 jobs in the four weeks ending Jan. 24.

For more on what the private data providers are saying about jobs, read: The unofficial jobs data is unambiguously discouraging 💼 and The crummy labor market is yielding a ‘tenure dividend’ for corporations 💰

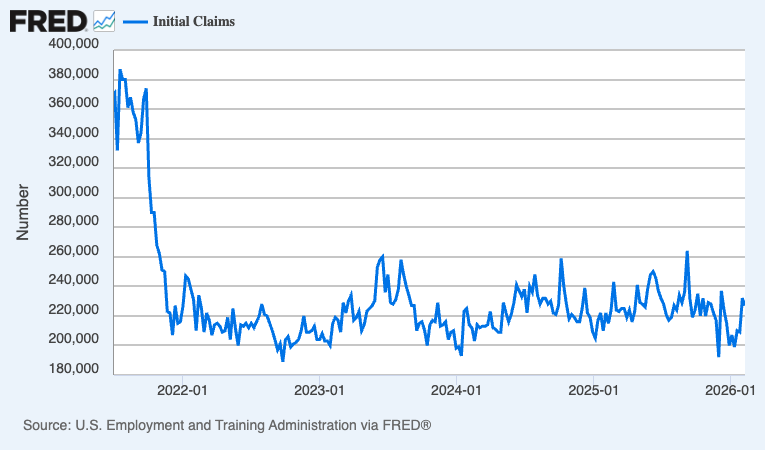

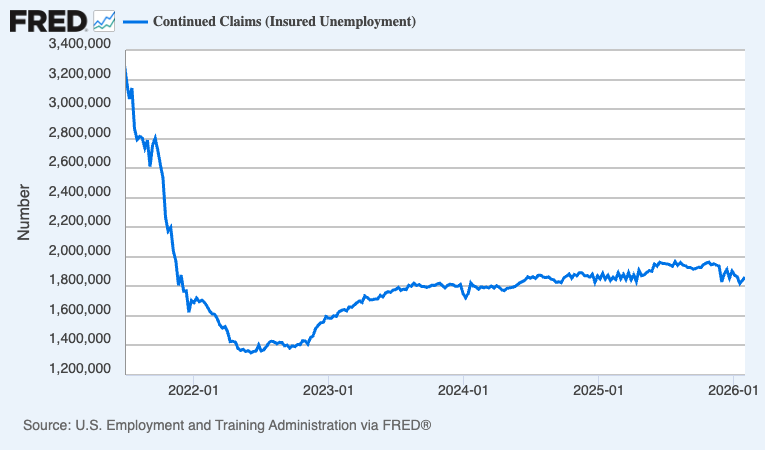

💼 New unemployment insurance claims tick lower, total ongoing claims rise. Initial claims for unemployment benefits declined to 227,000 during the week ending Feb. 7, down from 232,000 the week prior. This metric remains at levels historically associated with economic growth.

Insured unemployment, which captures those who continue to claim unemployment benefits, rose to 1.862 million during the week ending Jan. 31.

For more on the labor market, read: The next couple of years for the job market could be tough 🫤

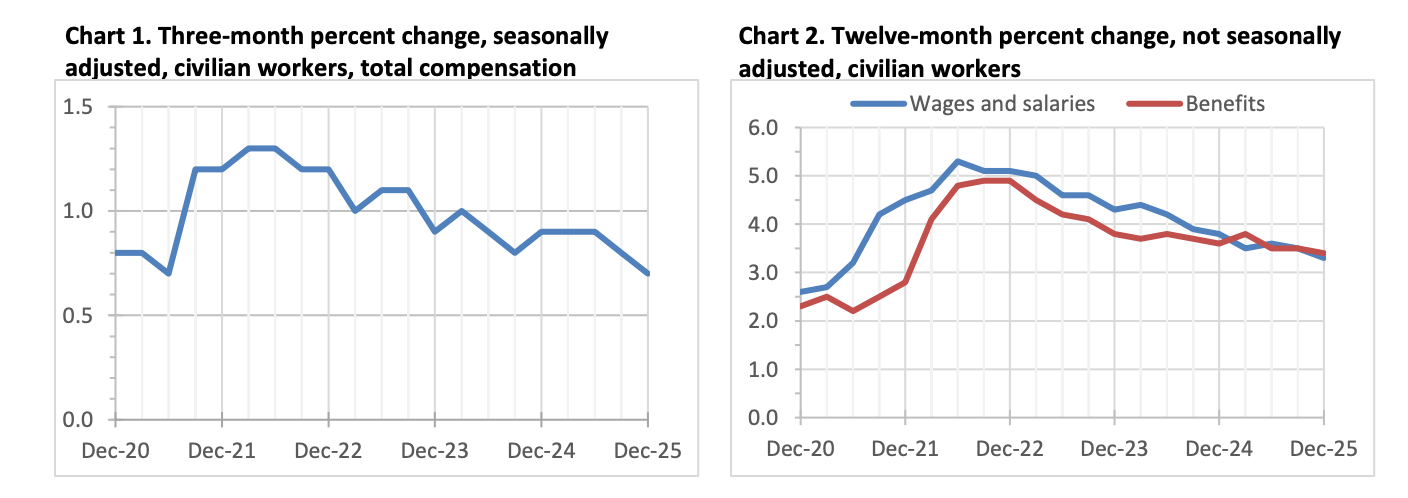

💵 Key labor costs metric cools. The employment cost index in Q4 was up 0.7% from the prior quarter.

For more on why policymakers are watching wage growth, read: Revisiting the key chart to watch amid the Fed's war on inflation 📈

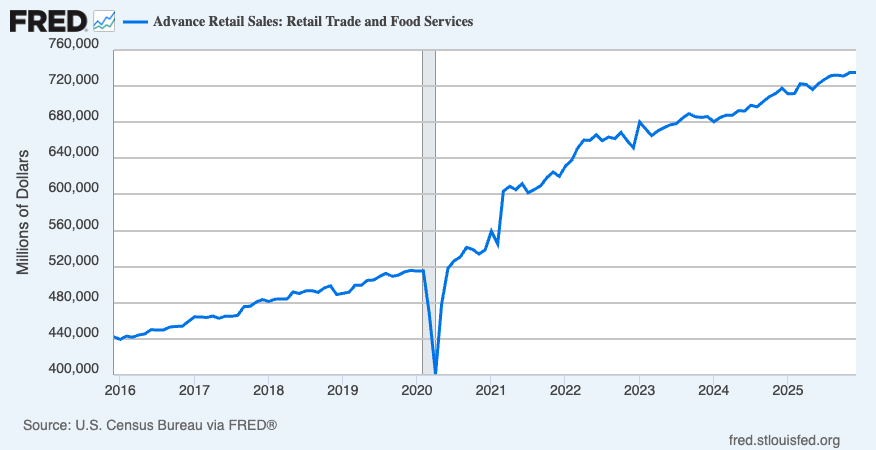

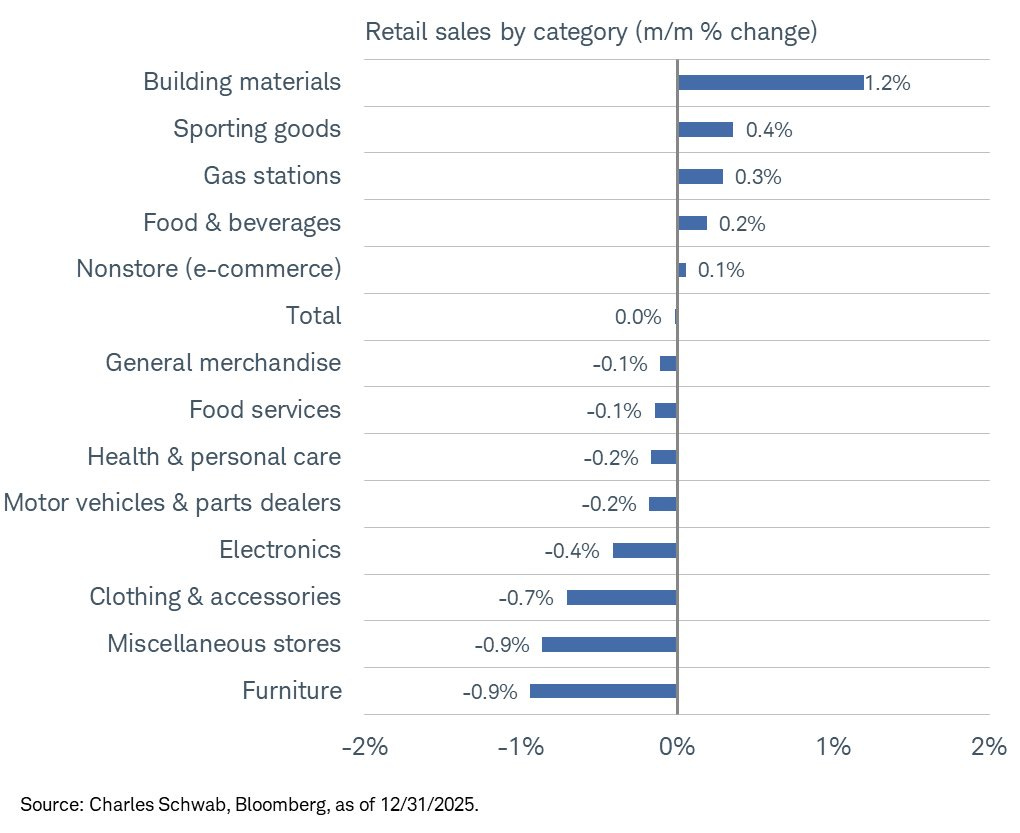

🛍️ Retail shopping activity was flat near record levels. Retail sales in December were largely unchanged from November levels, coming in at $734.97 billion.

Most retail categories declined.

For more on what’s bolstering spending, read: Consumer finances remain in good shape 💵

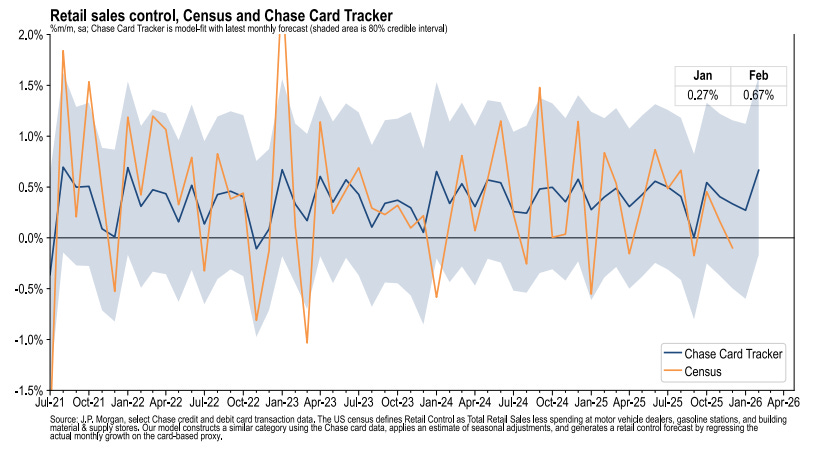

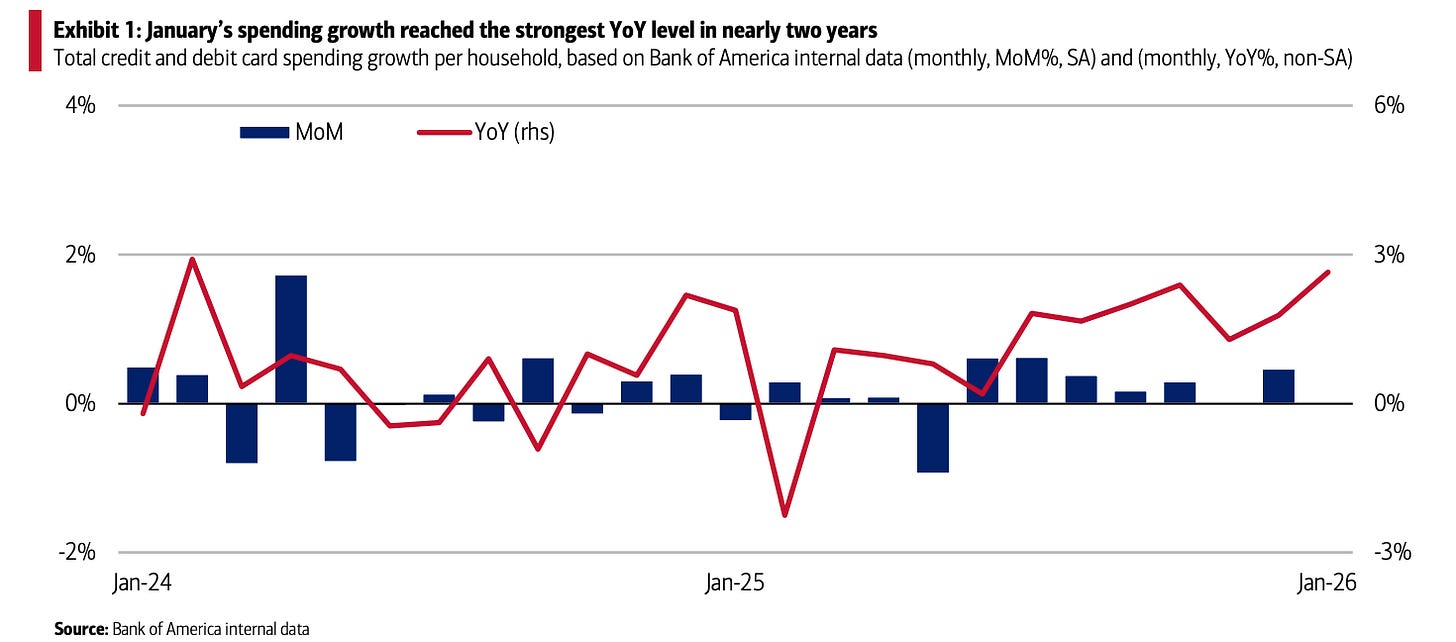

💳 Card spending data is holding up. From BofA: “Consumer spending showed solid resilience in January, with total card spending rising 2.6% year-over-year (YoY) — the strongest pace in nearly two years — despite weather‑related disruptions, according to Bank of America internal data.”

From JPMorgan: “As of 06 Feb 2026, our Chase Consumer Card spending data (unadjusted) was 4.5% above the same day last year. Based on the Chase Consumer Card data through 06 Feb 2026, our estimate of the US Census January control measure of retail sales m/m is 0.27%.“

Consumer spending data has looked a lot better than consumer sentiment readings. For more on this contradiction, read: We’re taking that vacation whether we like it or not 🛫 and Consumer finances remain in good shape 💵

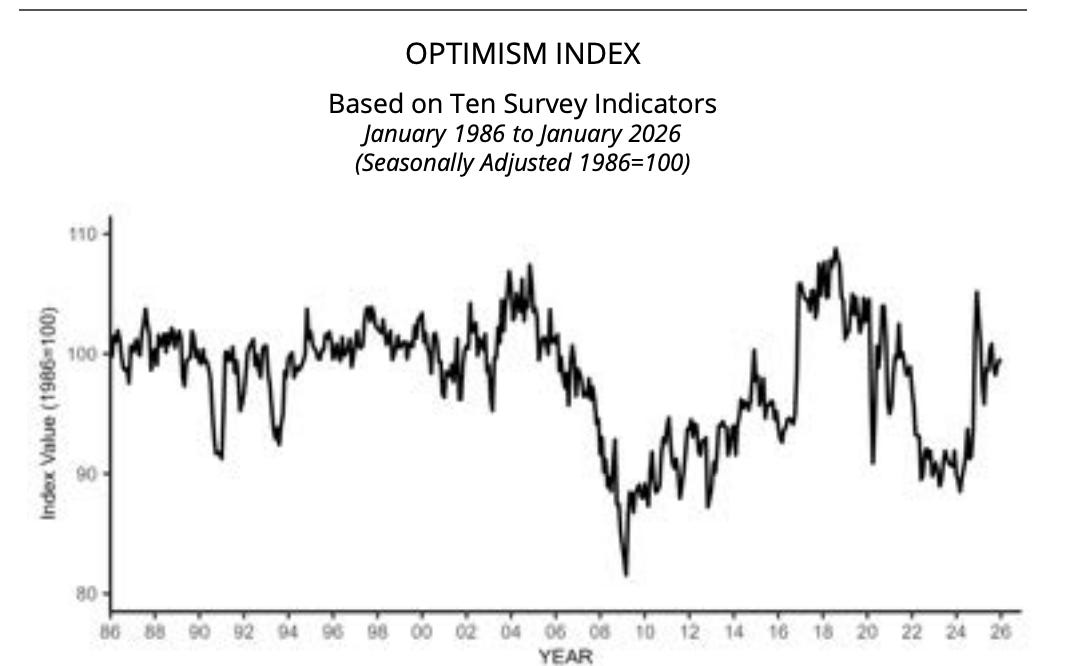

👎 Small business optimism ticks lower. The NFIB’s Small Business Optimism Index declined to 99.3 in January from 99.5 in December. From the NFIB: “While GDP is rising, small businesses are still waiting for noticeable economic growth. Despite this, more owners are reporting better business health and anticipating higher sales.”

Keep in mind that during times of perceived stress, soft survey data tends to be more exaggerated than actual hard data.

For more on this, read: What businesses do > what businesses say 🙊 and 4 sometimes-conflicting ways I’m thinking about the economy 😬😞😎🙃

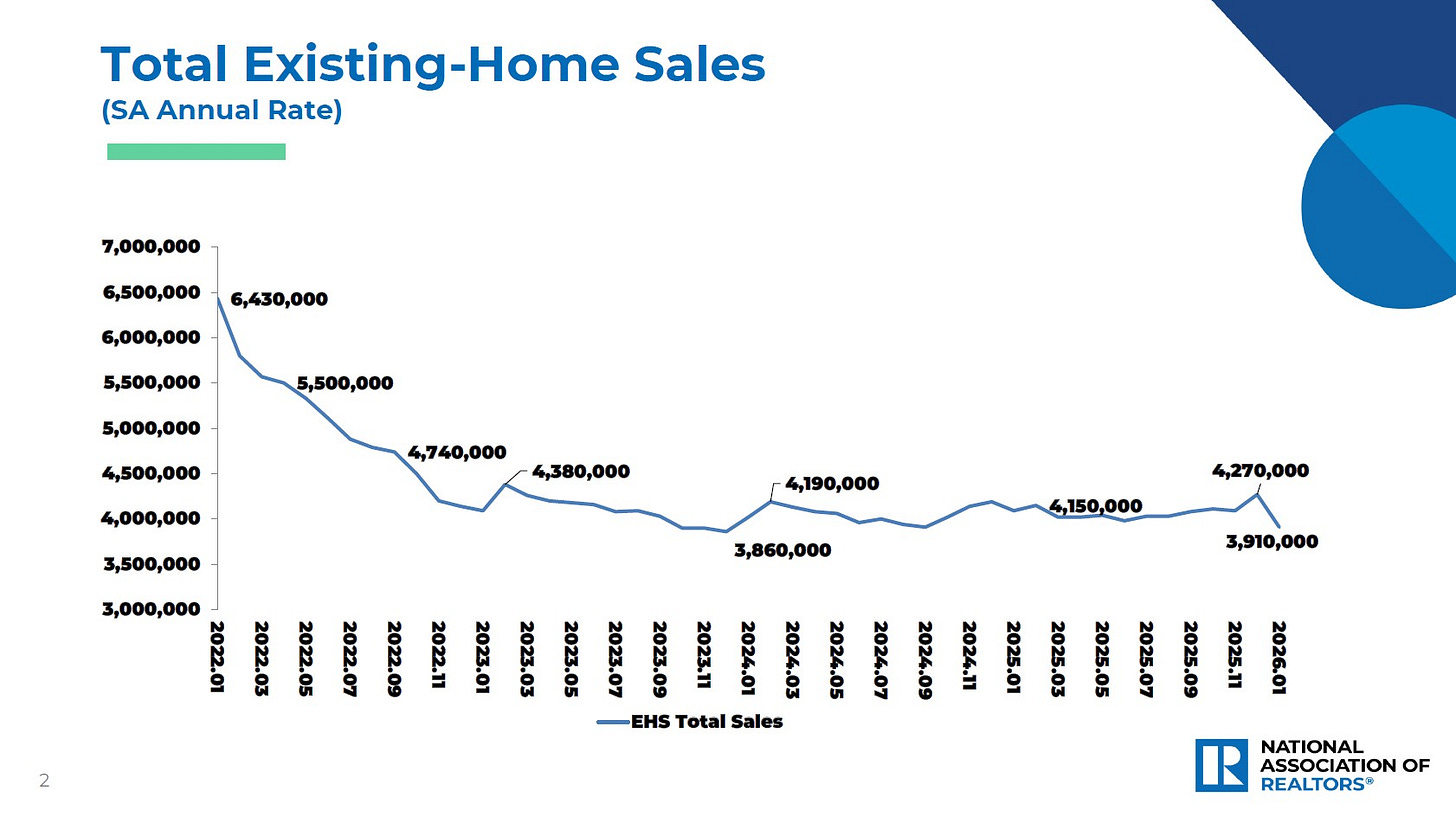

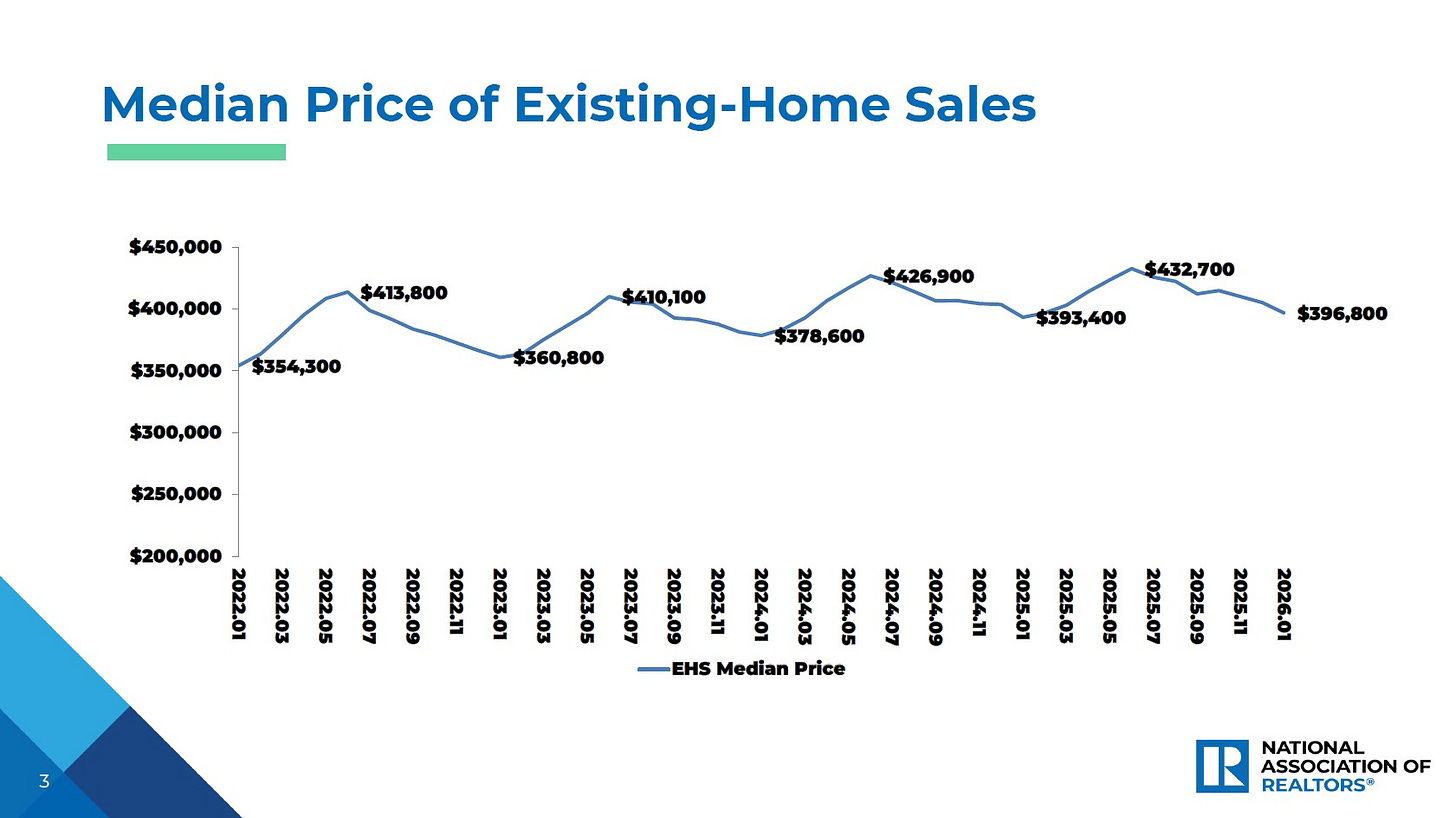

🏚 Home sales tumbled. Sales of previously owned homes fell 8.4% in January to an annualized rate of 3.91 million units. From NAR chief economist Lawrence Yun: “The decrease in sales is disappointing. The below-normal temperatures and above-normal precipitation this January make it harder than usual to assess the underlying driver of the decrease and determine if this month’s numbers are an aberration.”

Prices for previously owned homes declined from last month’s levels, but rose from year-ago levels. From the NAR: “The median existing-home sales price for all housing types in January was $396,800, up 0.9% from one year ago ($393,400) – the 31st consecutive month of year-over-year price increases.”

From Yun: “Due to low supply, the median home price reached a new high for the month of January. Homeowners are in a financially comfortable position as a result. Since January 2020, a typical homeowner would have accumulated $130,500 in housing wealth.”

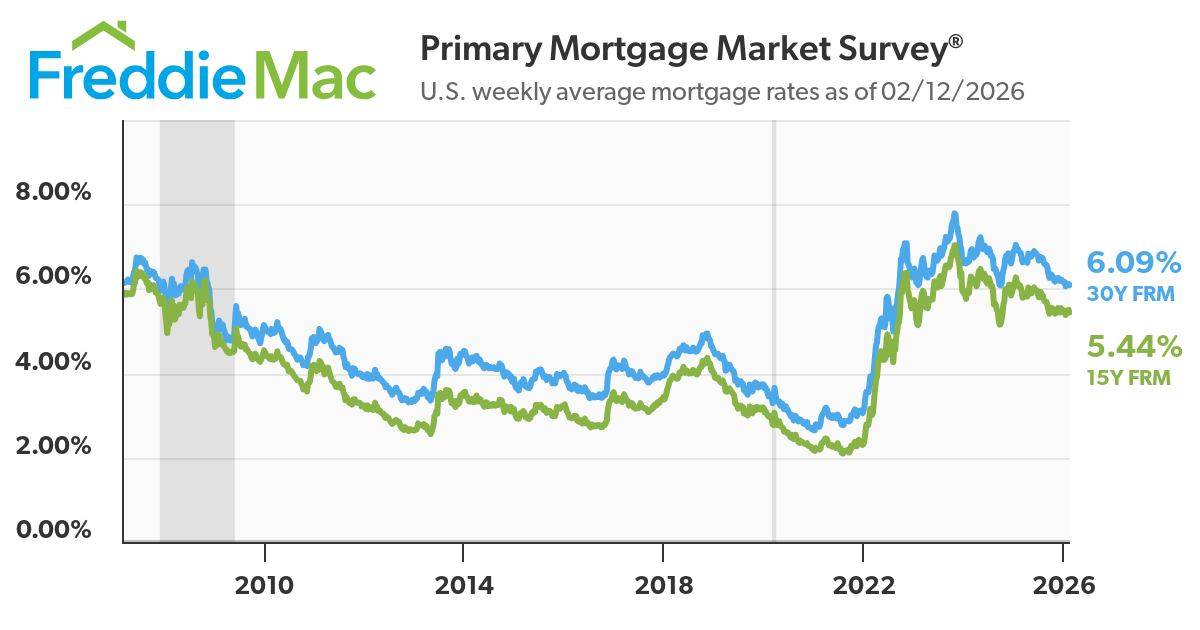

🏠 Mortgage rates tick lower. According to Freddie Mac, the average 30-year fixed-rate mortgage declined to 6.09%, down from 6.11% last week: “Bolstered by strong economic growth, a solid labor market and mortgage rates at three-year lows, housing affordability continues to measurably improve. These factors have caught the attention of many prospective homebuyers, driving purchase application activity higher than a year ago.”

As of Q3, there were 148.3 million housing units in the U.S., of which 86.9 million were owner-occupied and about 40% were mortgage-free. Of those carrying mortgage debt, almost all have fixed-rate mortgages, and most of those mortgages have rates that were locked in before rates surged from 2021 lows. All of this is to say: Most homeowners are not particularly sensitive to the small weekly movements in home prices or mortgage rates.

For more on mortgages and home prices, read: Why home prices and rents are creating all sorts of confusion about inflation 😖

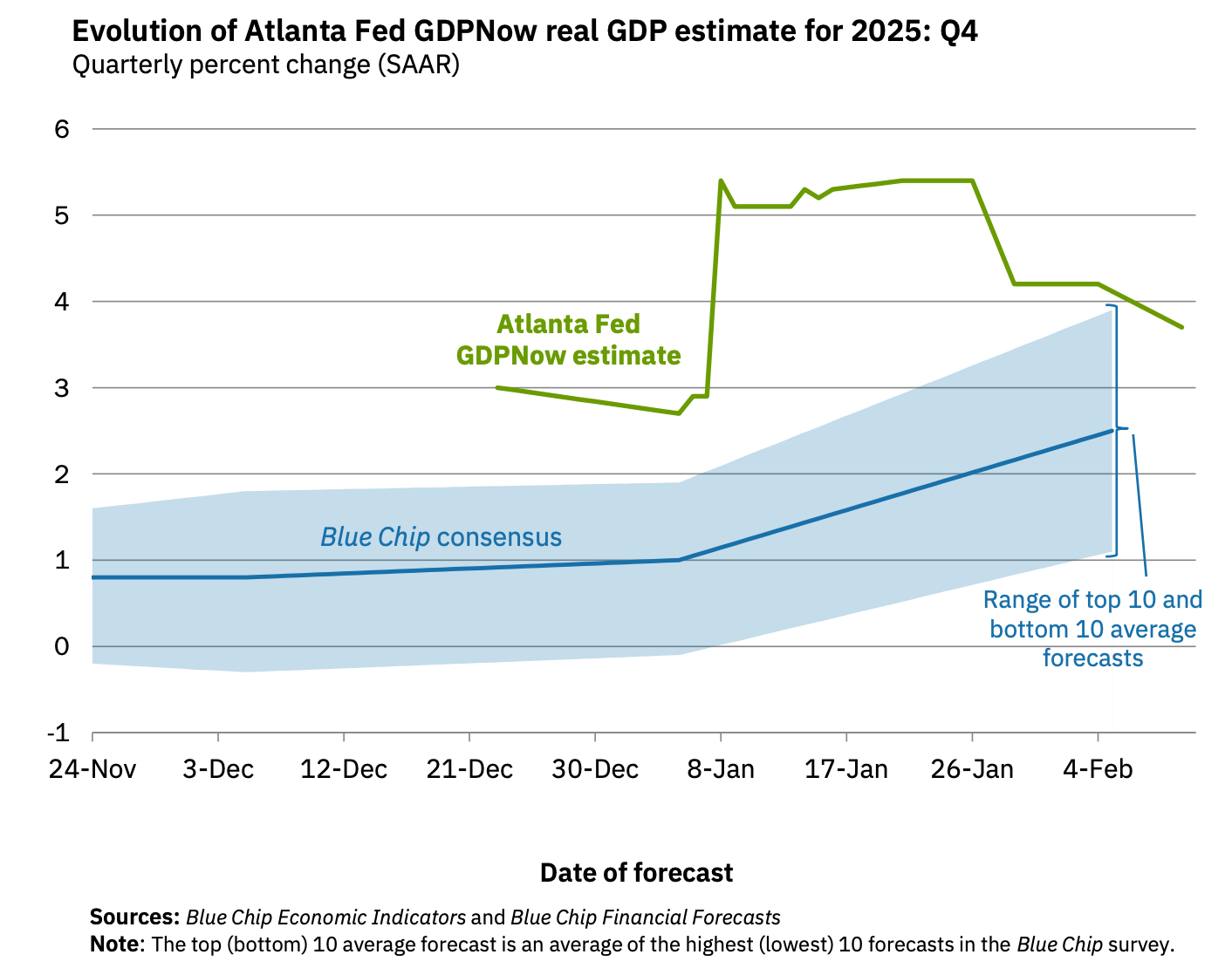

📈 Near-term GDP growth estimates are tracking positively. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model sees real GDP growth rising at a 3.7% rate in Q4.

For more on GDP and the economy, read: 9 once-hot economic charts that cooled 📉 and We’re at an economic tipping point ⚖️

Putting it all together 📋

Earnings look bullish: The long-term outlook for the stock market remains favorable, bolstered by expectations for years of earnings growth. And earnings are the most important driver of stock prices.

Demand is positive: Demand for goods and services remains positive, supported by healthy consumer and business balance sheets. Job creation, although cooling, appears to be modestly positive, and the Federal Reserve — having resolved the inflation crisis — shifted its focus toward supporting the labor market.

But growth is cooling: While the economy remains healthy, growth has normalized from much hotter levels earlier in the cycle. The economy is less “coiled” these days as major tailwinds like excess job openings and core capex orders have faded. It has become harder to argue that growth is destiny.

Actions speak louder than words: We are in an odd period, given that the hard economic data decoupled from the soft sentiment-oriented data. Consumer and business sentiment has been relatively poor, even as tangible consumer and business activity continues to grow and trend at record levels. From an investor’s perspective, what matters is that the hard economic data continues to hold up.

Stocks are not the economy: There’s a case to be made that the U.S. stock market could outperform the U.S. economy in the near term, thanks largely to positive operating leverage. Since the pandemic, companies have aggressively adjusted their cost structures. This came with strategic layoffs and investment in new equipment, including hardware powered by AI. These moves are resulting in positive operating leverage, which means a modest amount of sales growth — in the cooling economy — is translating to robust earnings growth.

Mind the ever-present risks: Of course, we should not get complacent. There will always be risks to worry about, such as U.S. political uncertainty, geopolitical turmoil, energy price volatility, and cyber attacks. There are also the dreaded unknowns. Any of these risks can flare up and spark short-term volatility in the markets.

Investing is never a smooth ride: There’s also the harsh reality that economic recessions and bear markets are developments that all long-term investors should expect as they build wealth in the markets. Always keep your stock market seat belts fastened.

Think long-term: For now, there’s no reason to believe there’ll be a challenge that the economy and the markets won’t overcome. The long game remains undefeated, and it’s a streak that long-term investors can expect to continue.

For more on how the macro story is evolving, check out the previous review of the macro crosscurrents. »

Key insights about the stock market 📈

Here’s a roundup of some of TKer’s most talked-about paid and free newsletters about the stock market. All of the headlines are hyperlinked to the archived pieces.

10 truths about the stock market 📈

The stock market can be an intimidating place: It’s real money on the line, there’s an overwhelming amount of information, and people have lost fortunes in it very quickly. But it’s also a place where thoughtful investors have long accumulated a lot of wealth. The primary difference between those two outlooks is related to misconceptions about the stock market that can lead people to make poor investment decisions.

The makeup of the S&P 500 is constantly changing 🔀

Passive investing is a concept usually associated with buying and holding a fund that tracks an index. And no passive investment strategy has attracted as much attention as buying an S&P 500 index fund. However, the S&P 500 — an index of 500 of the largest U.S. companies — is anything but a static set of 500 stocks.

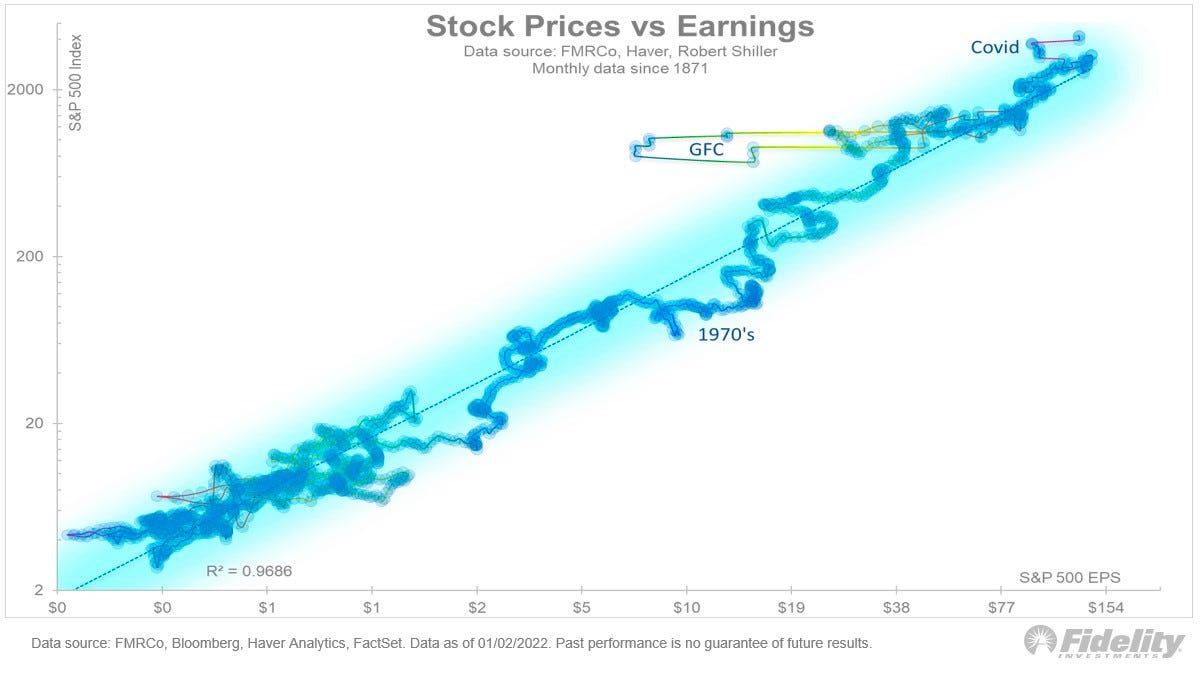

The key driver of stock prices: Earnings💰

For investors, anything you can ever learn about a company matters only if it also tells you something about earnings. That’s because long-term moves in a stock can ultimately be explained by the underlying company’s earnings, expectations for earnings, and uncertainty about those expectations for earnings. Over time, the relationship between stock prices and earnings has a very tight statistical relationship.

Stomach-churning stock market sell-offs are normal🎢

Investors should always be mentally prepared for some big sell-offs in the stock market. It’s part of the deal when you invest in an asset class that is sensitive to the constant flow of good and bad news. Since 1950, the S&P 500 has seen an average annual max drawdown (i.e., the biggest intra-year sell-off) of 14%.

How the stock market performed around recessions 📉📈

Every recession in history was different. And the range of stock performance around them varied greatly. There are two things worth noting. First, recessions have always been accompanied by a significant drawdown in stock prices. Second, the stock market bottomed and inflected upward long before recessions ended.

In the stock market, time pays ⏳

Since 1928, the S&P 500 has generated a positive total return more than 89% of the time over all five-year periods. Those are pretty good odds. When you extend the timeframe to 20 years, you’ll see that there’s never been a period where the S&P 500 didn’t generate a positive return.

What a strong dollar means for stocks 👑

While a strong dollar may be great news for Americans vacationing abroad and U.S. businesses importing goods from overseas, it’s a headwind for multinational U.S.-based corporations doing business in non-U.S. markets.

Stanley Druckenmiller's No. 1 piece of advice for novice investors 🧐

…you don't want to buy them when earnings are great, because what are they doing when their earnings are great? They go out and expand capacity. Three or four years later, there's overcapacity and they're losing money. What about when they're losing money? Well, then they’ve stopped building capacity. So three or four years later, capacity will have shrunk and their profit margins will be way up. So, you always have to sort of imagine the world the way it's going to be in 18 to 24 months as opposed to now. If you buy it now, you're buying into every single fad every single moment. Whereas if you envision the future, you're trying to imagine how that might be reflected differently in security prices.

Peter Lynch made a remarkably prescient market observation in 1994 🎯

Some event will come out of left field, and the market will go down, or the market will go up. Volatility will occur. Markets will continue to have these ups and downs. … Basic corporate profits have grown about 8% a year historically. So, corporate profits double about every nine years. The stock market ought to double about every nine years… The next 500 points, the next 600 points — I don’t know which way they’ll go… They’ll double again in eight or nine years after that. Because profits go up 8% a year, and stocks will follow. That's all there is to it.

Warren Buffett's 'fourth law of motion' 📉

Long ago, Sir Isaac Newton gave us three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Sir Isaac’s talents didn’t extend to investing: He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.” If he had not been traumatized by this loss, Sir Isaac might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases.

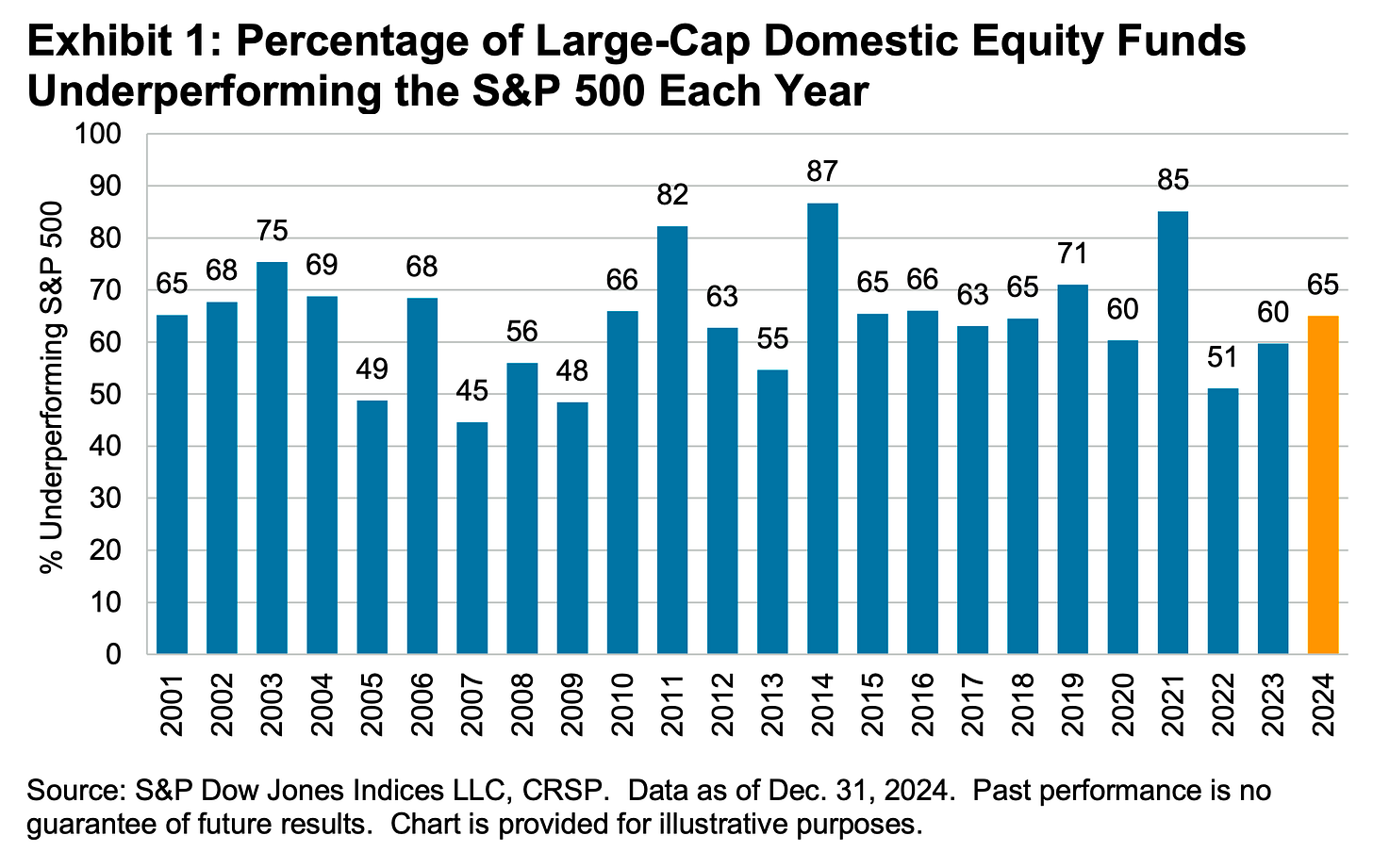

Most pros can’t beat the market 🥊

According to S&P Dow Jones Indices (SPDJI), 65% of U.S. large-cap equity fund managers underperformed the S&P 500 in 2024. As you stretch the time horizon, the numbers get even more dismal. Over three years, 85% underperformed. Over 10 years, 90% underperformed. And over 20 years, 92% underperformed. This 2023 performance follows 14 consecutive years in which the majority of fund managers in this category have lagged the index.

Proof that 'past performance is no guarantee of future results' 📊

Even if you are a fund manager who generated industry-leading returns in one year, history says it’s an almost insurmountable task to stay on top consistently in subsequent years. According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, just 4.21% of all U.S. equity funds in the top half of performance during the first year were able to remain in the top during the four subsequent years. Only 2.42% of U.S. large-cap funds remained in the top half

SPDJI’s report also considered fund performance relative to their benchmarks over the past three years. Of 738 U.S. large-cap equity funds tracked by SPDJI, 50.68% beat the S&P 500 in 2022. Just 5.08% beat the S&P in the two years ending 2023. And only 2.14% of the funds beat the index over the three years ending in 2024.

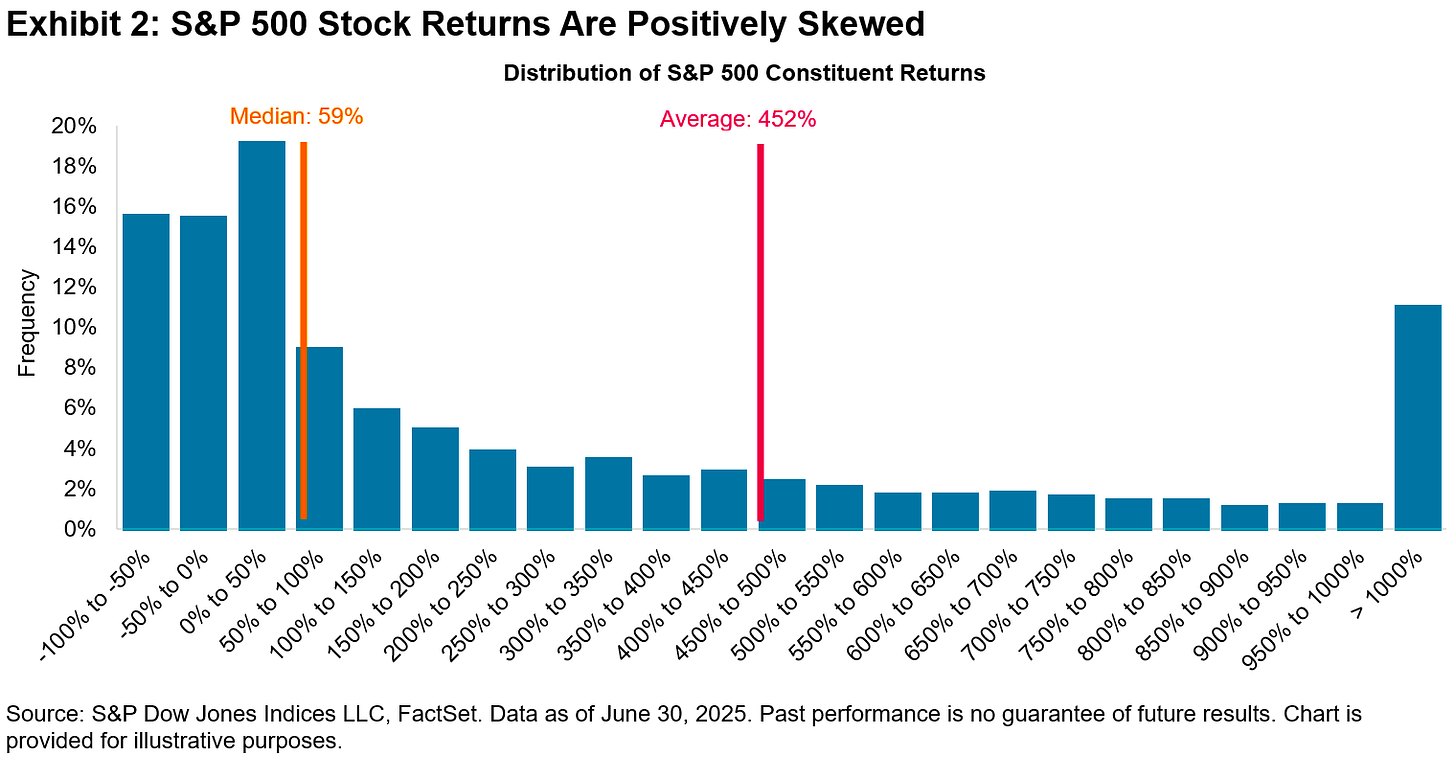

The odds are stacked against stock pickers 🎲

Picking stocks in an attempt to beat market averages is an incredibly challenging and sometimes money-losing effort. Most professional stock pickers aren’t able to do this consistently. One of the reasons for this is that most stocks don’t deliver above-average returns. According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, only 19% of the stocks in the S&P 500 outperformed the average stock’s return from 2001 to 2025. Over this period, the average return on an S&P 500 stock was 452%, while the median stock rose by just 59%.